- Home

- Banker, Ashok K

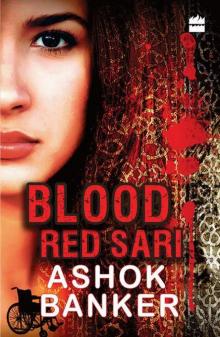

BLOOD RED SARI

BLOOD RED SARI Read online

BLOOD RED SARI

Kali Rising

Book 1

Ashok Banker

HarperCollins Publishers India

Epigraph

One of the undersides of globalization, human trafficking exists in at least 127 countries … the second most lucrative illicit enterprise in the world after drug trafficking, it is also the fastest growing, with global profits estimated at $44.3 billion USD per year.

– International Labor Organization and United Nations

The number of people held in slavery worldwide is estimated to be between 12 and 27 million, more than at any time in world history. A large proportion of the victims are women and children.

– U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

India’s home secretary Madhukar Gupta remarked that at least 100 million people were involved in human trafficking in India. ‘The number of trafficked persons is difficult to determine due to the secrecy and clandestine nature of the crime.’

– cnn.com

India may be the epicenter for human trafficking.

– freedomcenter.org

iam redit et Virgo

Translation: Now returns Justice

– Virgil

For

May Smith, grandmother

Sheila D’Souza, mother

Bithika Jain, wife

Yashka Banker, daughter

You made me the boy I was,

The man I grew up to be,

The husband and father I have become,

And the person I aspire to be someday.

And for Willow,

Who taught me that even ‘human’

Is too narrow-minded a classification.

We are all one in our separate skins.

Contents

Epigraph

Dedication

Prologue: India

Karkidakam

One:

1.1

1.2

1.3

Two:

2.1

2.2

2.3

Three:

3.1

3.2

3.3

Four:

4.1

4.2

4.3

Five:

5.1

5.2

5.3

Six:

6.1

6.2

6.3

Seven:

7.1

7.2

7.3

Chi Kou Ri

Eight:

8.1

8.2

8.3

Nine:

9.1

9.2

9.3

Ten:

10.1

10.2

10.3

Eleven:

11.1

11.2

11.3

Twelve:

12.1

12.2

12.3

Thirteen:

13.1

13.2

13.3

Fourteen:

14.1

14.2

14.3

Fifteen:

15.1

15.2

15.3

About the Author

Author’s Note

Copyright

Prologue: India

Kali Pujo

An Appeasement

ON A SEARING AFTERNOON in May, I caught a tram to the oldest neighbourhood in the city. This is the place for which Kolkata, or Calcutta as the British pronounced it, was named. Kali-ghat, the sacred burning ghat of goddess Kali, which is now just another debilitated inner city neighbourhood, still houses the ancient Kali temple which once formed the centre of the city. It was a Sunday and the streets were quiet and deserted as I got off the tram and walked the last few kilometres through winding cobbled streets. Heat shimmered on the street, making the departing tram seem to levitate before it passed into obscurity. A stray bitch, teats bulging with unconsumed and probably hardened milk, muzzled a pile of rotting watermelon rinds beneath a fruit seller’s handcart. I glimpsed a trickle of blood oozing from her swollen genitalia as I passed by. If the swollen lactose glands didn’t kill her, the haemorrhaging certainly would.

The fruit seller, dozing on the footpath beside the cart, glanced up at me with bulging Bengali eyes, clutching his watermelon knife. The blade had been re-sharpened so many times that it was little more than a crescent sliver. ‘Melon khaabey?’ he asked hopefully. I ignored him and walked on. My destination was the temple, where I meant to offer pujo and express my gratitude to the goddess as promised. I had fasted all day to keep myself pure for the offering.

Kali, in ancient Indian mythology, is one of the infinite forms of Devi, the eternal goddess, repository of all feminine power. The Puranas, literally ‘ancient tales’, tell of a time when the devas, the myriad gods of the Vedic pantheon, were troubled by new enemies. The asuras, their eternal rivals, had four great champions with great powers of destruction. Try as they might, the devas could not defeat the new threat. The demons rampaged and ravaged the realms of the gods and mortals for an eternity until finally, exhausted and at their wits’ end, the devas took refuge in Almighty Brahma, the Creator. The other partners who made up the great Trimurti of the Vedic pantheon – Vishnu the Preserver and Shiva the Destroyer – combined their fury with that of Brahma and the other gods, and a terrible brilliance emanated from each of their faces. Combining with the evanescence of a thousand suns and the spiritual strength of the great sage Katyayana, the devas produced a mighty new champion in the aspect of the goddess Kali. From the deva Mahendra was formed her face. From Agni, Lord of Fire, came her eyes. From Yama, Lord of Death and Dharma, her hair. From Vishnu, the champion of mortalkind and upholder of life, her eighteen hands. From Indra, the general of the army of the devas, her viscera. From Varuna, Lord of the Ocean, her hips and thighs. From Brahma the Creator, her feet. From Surya, the sun god, her toes. From Prajapati, the seed-giver of all life, the teeth. From the eight Vasus, her fingers. From Yaksa, her nose. From Vayu the Lord of the Wind, her ears. And from the ascetic tapasya of Maharishi Katyayana at whose ashram their energies converged, she received her seductive eyebrows.

She was given gifts too – weapons and objects of beauty and great power – by the various devas. When her creation was complete and her armaments assembled, she mounted a lion and went to the highest peak of the Vindhya Range, from whence she launched her campaign of vengeance against the supposedly indomitable asuras – an epic rampage of bloodlust that has few equals even in the blood-spattered annals of Hindu mythology. She was given many names, the foremost among them being Durga, Katyayani, Chamundi, and of course, Kali.

It was to her shrine that I now came, to perform pujo, the prayer ritual to appease and please her. I paused at the entrance to the narrow alley that led to the temple precinct. The last time I had come here, it had been with rage in my heart and a curse on my lips. I had furiously demanded that Kali deliver to me the goal I desired, or else. So frustrated had I been at that time, I had threatened the goddess herself. It was the nadir of the worst phase of a not wonderful life.

Now I returned bearing gifts and a light heart. I had in the folds of my sari a gold chain that I intended to give to Kali. I had bought it at a jeweller’s in Park Street for more money than the fruit seller I had walked by would probably earn in his lifetime. The comb, kohl, lip colour and other cosmetics that one customarily gifted to the goddess during the ritual, I would purchase from the pundits at the temple. I also intended to put five thousand rupees into the daanpeti, the donation box of the temple. I would pay to feed all the residents of a girls’ orphanage in Dakshineshwar once a week for a year as well. And of course, how could I forget the sari it

was customary to gift the goddess: a sari in a colour that matched her blood-soaked rampage.

There were other offerings too, for I had money to spend and to spare. And limitless gratitude. It had been a good year. A very good year. The more so since it came on the heels of a hard and dangerous life. Not everything that had happened in that year had been good. Some awful, terrible things had taken place. I had made two of the dearest friends I had found in my entire life and lost one of them under circumstances so tragic that it still made me cry in impotent rage when I remembered. There had been a series of events epic enough to rival the tortuously winding story-cycles of ancient Indian Puranas; and when trapped within the deepest, darkest days of that period, I hadn’t expected to come out of it alive. Yet somehow, I had not just survived, I had prospered. Hugely. And now I wanted to show my gratitude, to share the overwhelming sense of relief and joy I now felt, with the goddess I had cursed and abused before leaving Kolkata.

The line was short. The annual Durga Puja festival had just ended – nine days and nights of celebration devoted to nine aspects of the Eternal Goddess – and my fellow Bengalis were mostly home recovering. The woman in front of me in the line was young, barely more than a teenager. She had a Blackberry clutched in her hands and was pressing buttons non-stop, tweeting about her first trip to Kolkata, her first visit to the Kali temple, the fashionable club she was going to party at with her posse that night, how she couldn’t understand why people clung to these ancient pagan customs in this modern age, yada yada yada. The last glimpse I had of her screen, she was updating her Facebook status to continue the grumbling there as well. I resisted the urge to grab her and shake her by the shoulders. In many ways, I was her; I was less than a decade older, perhaps, but in other ways, I was centuries older. And had always been. I was relieved when her turn came and she moved on, head still lowered, punching away.

The temple bells began to toll as I stood there, steel thali in hand, the heavy Bengali silk sari feeling awkward on my jeans-and-shirt-accustomed body in the sweltering sunshine. Before, they had always sounded to my angry ears like a lost goddess raging to an unjust world. Now, they sounded sad rather than angry, like a dirge, a toll, a commemoration of lost friends, and an ending.

I climbed the steps of the temple, the ancient stone cool beneath my bare soles, its surface worn smooth by the footfalls of countless devotees over the centuries, seeking solace, appeasement, virility, wealth and the thousand other things people prayed for. I had sought only one thing when I came here last, and somehow, impossibly, I had received it. I had looked into the hot eyes of Kali and demanded, cried out for justice.

Or was it vengeance?

Sometimes, it is hard to tell the difference.

Karkidakam

Day of the Dead

One

1.1

EVER SINCE SHE WAS a little girl yay high, she had loved Karkidakam.

Ever since she was a little girl yay high, she had hated Karkidakam.

She hated it for being the death knell of summer vacations, the months when they could be as lazy as fat flies. When mangoes were in season and they could have their fill, just wander into the kitchen reading a dog-eared copy of a favourite book, pick up a mango from the crate – the top layer had the ripe ones – bite into it, skin and all, and feel the sticky juices spill down their chins. When they could tumble out of bed and race the dogs down to the beach, toothbrushes and Colgate clutched in their fists, and brush their teeth in the surf while jumping sideways like crazy crabs every time the tide roared in. Afternoons they might spend collecting coral or reading and dozing and talking or all three together in the shade of the palms on the cliff, while the dogs lay upside down for their tummies to be scratched. Sometimes, they caught a ride out on Achchan’s boat to fish. Once, Lalima brought a karachemmeen one-and-a-half times as long as herself; and then they ate karachemmeen for breakfast, lunch and dinner the next three days. Evenings they ate sukhiyan at Mathews’s and watched the sunset. It was an unspoken rule; they never missed a sunset and never ate sukhiyan anywhere except at Mathews’s, don’t ask why.

But then came Karkidakam and amavasi, and Varkala was overrun by hordes of the Undead. That was what Lalima called those who had not made it to the other realm one summer and the name just stuck. Ezhu had returned from one of his trips from Do-Buy with one of those shiny new bissyaars – a National Panasonic with remote! (he always said it that way, italicised and with the exclamation at the end) – and one of the tapes he brought back was Night of the Living Dead. They watched it one breathless night without Atta or Acchi knowing, and for weeks afterwards, ‘They’re coming to get you, Barbara!’ became a permanent fixture in their vocabulary. So when the hordes of pilgrims began falling off the buses and rolling through their backyard on amavasi, their lives came to a standstill. The beach, their beach, was gone, taken over by an army of the Undead, lurking around, praying, offering vavu bali, indulging in papanasam, eating their sukhiyan at Mathews’s, stealing their sunset. The horror, the horror. And afterwards, even though the invasion lasted for barely a day or two, the beach and its environs were always so filthy with the refuse and leftovers that it just wasn’t the same. There were neat mundu-sets left everywhere, ostensibly for departed relatives, and while they understood the reason why people did it, it was irritating to keep tripping over little piles of cloth everywhere in their backyard, not to mention the fact that none of these mundu neriyathu could actually be used by any living person because that would be inauspicious.

So Anita also hated Karkidakam, though hated is probably too strong a word. It was just that it marked the end of the summer fun. The fact that it was on an amavasi day in Karkidakam that Lalima’s parents left for the UAE, with her in tow, only served to permanently etch the day in her memory as a really sucky one.

So of course, it had to be on vavu bali day that she got the news that Lalima had passed away. Philip called. He didn’t have her cell phone number so he called the old landline. She stood by the telephone in the living room, still holding the instrument in her hand as the dial tone droned sonorously into her ear. Finally Mrs Matondkar stopped rocking, turned to look at her, and barked, ‘What, you’re having silent conversation?’

She put down the phone which rattled on the cradle before settling in. Mrs Matondkar saw the news written on Anita’s face like a creepy crawly on a business news channel. ‘Who died?’

How to describe Lalima? How to sum up a relationship, a person, a lifetime of memories – even if most of that lifetime had been spent apart? How to put it all into one concise word, neatly embossed on a plaque or a tombstone? Best friend? First love? The sister she had never had? All of the above? How could she convey what Lalima had meant to this old flatulent landlady who regarded same-sex relationships as an abomination in the eyes of God?

‘My best friend.’

Anita sat down on the little cane stool she kept by the telephone stand. For some reason, it was a foot high while the telephone itself was placed on a jutting wooden stand four feet high. It left her sitting with the telephone above her head, like a hovering bird. The stool and the telephone were in the main passageway of the flat, just inside the front door, and as she sat there, a package slid through the mail slot and fell with a heavy thud to the floor. It was a yellow manila document envelope with her name written on it with a black marker. She ignored it and buried her face in her hands and stayed that way for a while. She didn’t hear Mrs Matondkar wrestling herself out of her rocking chair, but at some point the old lady appeared beside her and placed a heavy hand that smelt of roasted channa on Anita’s head.

She said nothing; just kept her hand there.

After a moment or two, she turned and shuffled back to the rocking chair. She farted as she lowered her not inconsiderable bulk into its welcoming embrace. The squeaking began again. That was Mrs Matondkar’s way of consoling her. It was more affection or sympathy than she had shown Anita since she had come to stay at her place as a payi

ng guest seven years ago.

Finally, Anita rose from the stool, somehow avoided hitting her head against the telephone stand, picked up the envelope from the doormat, and turned towards her room. She would call the airlines to book a flight to Thiruvananthapuram, or maybe just pack a small bag and head straight to the airport. It being late evening on a weekday, Mumbai traffic would be horrendous as always, and the sooner she got going, the sooner she could be on a plane heading home. It would be the first time in thirteen years that she was going home. It felt like a lifetime.

The Undead would have left by the time she reached, although the piles of cloth would still be choking the beaches.

Somewhere in there, perhaps, was a pile for Lalima.

1.2

THE SECURITY GUARD OF the building was waiting when she pulled into her parking spot. He salaamed her as she shifted herself from the driving seat of the car to her wheelchair. He knew better than to offer to help and stood by watching with sympathy till she had completed the transfer, locked the car door, and started rolling towards the entrance of the building. It was early yet, and though some idiot was accelerating too fast and honking too much as he roared past, Sector A Pocket C was one of the quietest, most peaceful parts of Vasant Kunj. Most of the residents of the old Lutyen’s era building were high court lawyers who operated out of their chambers at the court premises. She was the only one who ‘worked from home’ even though she lived on the Gurgaon–Mehrauli highway. She used this apartment as an office. It was against regulations to operate a business practice and she had experienced some grief over it from a few of her less tolerant neighbours at first, but her physical condition and history helped ameliorate their attitude; the fact that she only saw clients at the chambers and used this place more for research and as a kind of back office pacified them. Now, she got a few glares from time to time, but those were mostly for the dogs.

She recognized the security guard as the one who usually worked the night shift, a tall Jat who was more polite than most of his brethren.

BLOOD RED SARI

BLOOD RED SARI