- Home

- Banker, Ashok K

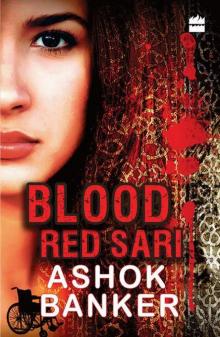

BLOOD RED SARI Page 3

BLOOD RED SARI Read online

Page 3

She shuddered and was about to turn away from the rusting hulk when something caught her eye. She leaned over, frowning, and peered through the murky filth coating the rear left passenger window. What was that? It looked like a chain of some sort, attached to a leather collar. Yes, a dog collar and chain. What was it doing inside the car? Had they been keeping a dog in there? But why inside the car? And those brown splotches and dried patches on the faded dirty upholstery, surely they couldn’t be … blood?

A gust of sea breeze, redolent of salt and fish, swept through the grove of kallu palms behind her family’s property, and the resulting shirring sound was a soothing reminder of childhood afternoons spent daydreaming or reading with Lalima. It made her grieve again for those lost years and for the years that could have been, should have been. Perhaps that was why she didn’t hear someone approaching behind her.

Something cold and hard pressed down on her right temple, causing her to freeze instinctively. Her eyes cut right briefly and she had a sense of a pair of long dark cylinders looming in her peripheral vision.

‘Well, well,’ said a raspy voice that she instantly recognized as Isaac’s. ‘The prodigal daughter returns. Didn’t you read the sign, sister dearest?’

She kept her voice deliberately casual and sarcastic, knowing that displaying fear would only worsen her situation. ‘I forgot my glasses in my ass. Could you fetch them, please?’

He cocked the shotgun in response; she could feel the reverberations of the bolt in her skull, the barrels were pressing that hard against her head.

‘I referred to the sign that read “Trespassers will be Prostituted”.’

She kept her hands still, but moved her fingers just enough to snap them smartly. ‘Of course. And you would be the friendly neighbourhood Pimp-in-Charge, right?’

He made a harsh throaty sound, then the pressure of the shotgun left her head just long enough for him to swing the length of the gun around to whack her with the wooden grip; a hard whack, hard enough to dislocate a shoulder or concuss her.

She was ready for it, though. And moved cobra quick to meet it.

2.2

IT WAS ONE OF those days. Due to the renovation work going on in the courtroom that was usually used for regular hearing matters of the category, court was being held in the extension building where accessibility was never as good as in the main complex. Then, someone had unloaded several boxes of court documents from a vehicle on the access ramp and Nachiketa had to wait several frustrating minutes for the boxes to be moved so that she could roll into the building. Finally, some good Samaritan did the needful, and she gritted her teeth and thanked him, hating how it made her feel, hating that someone had to take pity on her. She promised herself that she would file a complaint, but even as she rolled into the courtroom, she forgot all about it. They were there today. In force. The whole lot of them.

The Shah family: her mother-in-law glowering at her with those beady thyroidical eyes; her two sisters-in-law, both with their mother’s bulging optics and almost comically identical glare; assorted uncles and aunts and cousins and god knew who else; and of course, at the end of the line, looking a little bit fatter and angrier as he seemed to look each time she saw him, her great pati parmeshwar – husband who was like a god. Never mind that he was a mean, nasty, misogynistic, money-grubby son of a bitch, he was her husband, and that itself made him a god according to the ‘values’ of their community. She dearly wished she wasn’t confined to this wheelchair only so she could prostrate herself before him, touch his feet one last time and then grab hold of his ankles and send him crashing to the floor, hopefully breaking the bastard’s neck. She let none of this show outwardly, of course, greeting the court clerk politely and slipping him the case brief and waiting patiently till he informed her that her case number was indeed on the top of the docket for the day. That was satisfaction enough for her, because today was judgment day, hopefully, and it would be so, so sweet to see the expressions on their fat faces as Justice D.K. Pathak laid down the law.

But when the judge swept into court, she realized with a shock that it wasn’t D.K. Pathak. It was Honourable Mr Justice R.K. Jain instead. How had that happened? She tried to catch the clerk’s eye, but he was engrossed in the usual business of sorting and sifting through briefs to pass on to the chair in the correct order. She thought of sending Shonali an SMS asking her what was going on, but it would have been pointless. Besides, the DHC had probably started using the much-threatened jamming device due to the ongoing Judges’ Assets case that was going on in camera. In any case, court was already in session now and the clerk was already reading out the list of case numbers and noting the extension dates for each one.

Then she noticed the expressions on their faces. The Shah dynasty of Shahibaug. They seemed curiously content. That was when she felt the first whiff of suspicion. She tried to rack her brains to remember if R.K. Jain was one of those rumoured to be a ‘pliable’ judge, which was the preferred euphemism among her esteemed colleagues. She had no idea, but surely their mass presence here, combined with the unexpected change of the presiding judge, that too on judgment day, signalled that something black and squirmy had likely fallen into the lentils, na? By then her number had been called and the judge was already making disapproving noises at her and the defending party’s lawyers, who were all suited-booted hotshots from a firm large enough that her entire practice would probably fit into a single overnight case used as carry-on baggage by one of their junior-most assistants. She suddenly lost all the good mojo she had brought with her and knew that fate had just tossed the horseshoe at her skull. Clang.

‘Begging your pardon, but Honorable Mr D.K. Pathak is well appraised of this matter and was about to pass summary judgment, so please Your Honour.’

The Honourable Mr Justice R.K. Jain stared down at her bleakly from his bench, and in a long-suffering tone mumbled something about D.K. Pathak proceeding on indefinite leave for personal reasons and that he would be taking over D.K. Pathak’s caseload, if, of course, Madam Attorney-at-Bar Mrs Nachiketa Shah had no objections to the same. That drew a few titters from the front row, and she hardly needed to turn her head to know the source.

She tried again, asking for an extension, a continuation, time to review, etc., but she was summarily turned down each time with a bored, disdainful yet curiously methodical precision that told her all she needed to know about the good justice R.K. Jain. Bought, sold, sealed, delivered. Giftwrapped with a red ribbon.

She was on the verge of giving up – if only for the day, that is, she had come much too far to ever truly give up – when she caught sight of a familiar set of faces. That perky young news reporter from NDTV News – or was it CNN IBN? One of the English news channels, at any rate. And several others. A whole shebang of TV and print news reporters all lined up and ready to byte. Of course. They were here for the Judges’ Assets matter. It was big news, headline and breaking-news stuff. Not her piddly little nobody-nothing case. But they were here nevertheless. And so was she. And if she was going to be railroaded and outmanoeuvred yet again by the great Shah dynasty, she was damn well going to kick in a few teeth, even if only metaphorically.

She turned back to the bench. ‘Honourable sir, I request you to consider the primary facts in the case one final time before passing summary judgment.’

R.K Jain frowned, and even the court clerk blinked rapidly and raised his head to peer owlishly at her from above his stacks of files and papers and chits. But before anyone could object, she was launched and rolling like an Olympic ski racer down a too-fast slope.

‘That man, my husband Shri Jignesh Ramchandra Shah, married me for one reason and one reason only: to use me to siphon off my family’s money. The truth was revealed immediately after the ceremony itself. Our honeymoon was cancelled because he cashed in the tickets and hotel reservations and kept the money, just as his mother and sisters took away every single one of the wedding presents. Over the next few weeks, every single thing of val

ue I had brought with me, including my personal jewellery, they took – by cajoling and pleading at first, then by demanding arrogantly, and finally by use of force. Then the demands began. He needed cash to shore up his new venture, a new car, a new flat. My parents were not badly off, but they didn’t possess unlimited means either. When my father tried to put his foot down, the abuse began. At first, I was only harangued and yelled at and slapped around a few times each day. Then I was beaten and locked into a storeroom and left for days without food or water or toilet facilities. Then the real horror began. My husband left on a business trip and my mother- and sisters-in-law came into the storeroom where I was sleeping in the dead of night and began to beat me mercilessly with cricket bats and stumps. All the time, they kept yelling at me that if I wouldn’t pay in cash, I would pay in kind. “Tara hadkanu maas kadi leisu” was a favourite phrase they shouted over and over again – which translates into “We will take even the marrow from your bones”.

‘When they had finished with me, I had seventeen major fractures, including two on the skull, a shattered hip, a smashed spine, a ruptured spleen and pancreas, a damaged kidney, a collapsed lung, three broken ribs, and I had miscarried and lost the foetus I had been carrying, of which even I was not aware at that point. I required fifty-eight stitches, fourteen hours on the operation table, three months in the ICU, over eight months in hospital, and another two years in physiotherapy before I was even fit enough to use a wheelchair independently. I am disabled for life and can never bear children or enjoy a normal life. esult of the considerable amounts already given to my husband’s family, and the medical expenses that followed, my family was thoroughly bankrupted. My father suffered a stroke and was subsequently paralysed. He died within the year after the Shahs attacked me. My mother developed a heart condition and succumbed to it three years later, and there is no doubt that the shock itself had reduced her life. I consider what the Shahs did to be nothing less than murder. Had they shot my parents dead, they could not have killed them more effectively. As for me, I have spent the subsequent eight years, not including the three years of hospitalization and therapy, attempting to bring the Shahs to justice for their acts. Today, finally, I came to this venerated court room to hear the summary judgment on my case. I await your Honourable decision with all grace and humility. Thank you, Your Honour.’

And she rolled back a metre from the bench, keeping her head down and eyes averted, praying that she hadn’t gone too far, that her little ‘performance’ had served to draw the media’s attention to her otherwise nondescript case and the judge’s attention to the presence of the media, in the hope that whatever backdoor deal the Shahs had worked with this R.K. Jain, it wouldn’t be immune to the glaring eye of the fourth estate.

2.3

SHEILA WAS DOING ABS when the men entered the gym.

She did cardio and abs three days a week, legs twice, weight training six times weekly, one major body part and one minor. Today was chest and triceps day. She had started with a ten-minute warm up on the treadmill, just to get her heart rate up and a little sweat going. Then she had started with flat bench presses: three sets of 60, 80 and 100 kgs, fifteen reps each set, thirty seconds between sets, then a two-minute break and a couple of tiny sips of an electrolyte drink to keep her salts balanced. She tended to sweat a lot once her heart rate crossed 135–140 and hence dehydrated easily. After that, incline bench presses, same weight, same reps and time. And finally, decline bench presses.

That earned her and her spotter a five-minute break each, during which she exchanged hellos with regulars and kept an eye on the trainers, both the private ones who got paid extra for every forty-five-minute workout session as well as the floor trainers who only got a salary. She preferred to promote floor trainers to private trainers because that motivated the salary earners who were eager to work hard and prove that they deserved their own set of clients and a cut of the extra fee paid for private training. She also paid a better percentage to the private trainers – 60 per cent as against the 30 or 40 per cent most gyms reluctantly shared. She was routinely called by private trainers from other nearby gyms, eager to bring their roster of clients with them to earn the extra commish she paid. But she rarely agreed because in her view the extra commish was to reward her own deserving trainers who had worked hard to build their own list of clients, rather than an incentive to poach trainers and clients from other gyms. It kept other gym owners from getting too resentful of her quick success and at least one had visited a couple of times and expressed grudging admiration for how she ran the place.

Five-minute break over, she did flat bench dumbbell flys, three sets of 25 kgs (two dumbbells made 50 kgs), 30 kgs and 35 kgs, twelve to fifteen reps each. The same thirty-second break between sets, two-minute break to sip on Enerzal. Repeat with incline, then decline. Then another five-minute respite, during which she greeted a group of young women who had just entered for their workout: the Dakshineshwar athletes in training. These were India’s best women boxers, wrestlers and weight lifters, many of them world class, all national-level or at least state-level champions, and Sheila had offered them a month of free workouts if they won a gold medal at the Commonwealth Games. They had won not one but two golds, one silver and a bronze, and she had generously upped the offer to three months of free workouts. The girls came by bus all the way from Dakshineshwar just to workout here, and livened up the place. It was great publicity and inspirational for the regular members to see these international-class athletes pushing the same weights and sweating it out on the same mats every day. New memberships had quadrupled by the second week before stabilizing at about twice the normal sign-up rate. Cheers and high-fives went up all around as they greeted her one by one and made the usual jibes about the ‘old woman’ who still liked to keep in shape. She was well liked by them all, not just for the free workouts, but because of something she had done for two of the girls a year ago, just before she started the gym, back in her ‘earlier life’, as she liked to say, though she never talked about that earlier life.

By the time the Dakshineshwar athletes settled into their own routines, good-naturedly joking in Bengali as they peeled off their tee shirts and stripped down to their shorts to reveal dark brown and near-black bodies compacted and tightened to perfection through hard training and punishing discipline, Sheila was on her third session: cable crossovers. Giving in to the temptation to show off a bit, she went way over her usual top pulling of 120 kgs, and tried for 160 kgs – 80 kgs on each end. The athletes whistled and cheered her on as even the members on the bank of cardio machines at the far end stopped looking at their plasma screens and Blackberrys long enough to watch, some with sneers of naked jealousy but mostly with bemused amazement.

She ended the session drained, and slumped down on the floor, sweat staining her pullover from under both arms, right down to her waist. Her breath steamed inside her hood as she sipped the orange-flavoured drink from a Bisleri bottle and got her wind back. Fuck. Who said she was too old? At thirty-seven, she could give most women half her age a run for their money. Mits, her spotter, crouched beside her, patting her on the back proudly, happy to be sharing the limelight with her boss, and rambled on about some new scandal in Bollywood. Sheila could never understand how Hindi films had encroached even into parochial Bengal which had once had a flourishing film industry of its own and whose bhadralok had refused to speak any language except their own beloved Bangla. Yet there it was: Mits spoke reverentially of Bollywood stars and films the way her fellow bhadralok had once revered Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen. Sheila sighed. The world had changed. The dampness started to feel cold in the air-conditioned gym and she began to take off the pullover, then stopped herself: the scars. Exposing them would invite too many questions. Let the past stay past.

She gave herself a break on the triceps. Over-extending her limit on the cable cross had already given them a pretty good workout. She settled for doing bench dips which worked out both her abs as well as strengthened her t

riceps further. She was in the middle of the fifth set of fifty with one more set to go after that when the men walked in.

BLOOD RED SARI

BLOOD RED SARI